How the Ancestors of a Russian Countess Changed The World

By Robert Golomb

If a 94-year old woman told you that her father was one of the pioneers in the field of sociology, his father- her grandfather- founded one of the first worker’s compensation systems in the world and her late husband’s great, great, great grandmother made a decision which proved instrumental to America winning the Revolutionary War, you would probably believe she made up these claims.

If so, you would be wrong. A beautiful 94-year old Russian born woman named Countess Tatiana Bobrinkskoy offered those very same claims to me when I interviewed her last week. And I wisely and correctly believed every word she told me.

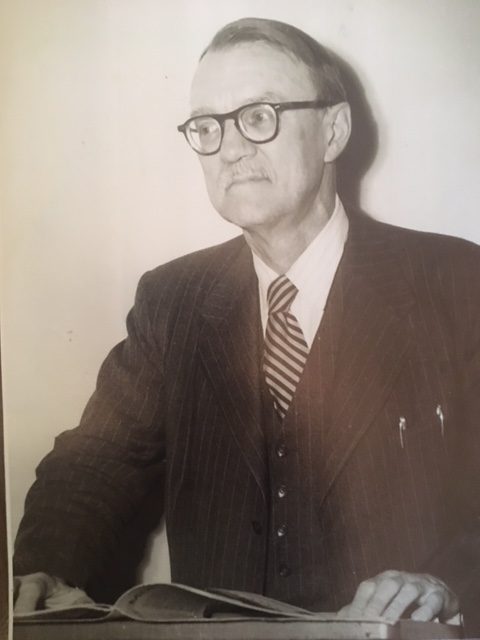

“Let’s just start with my father first”, she stated. “His books and essays on the then nascent field of sociology were considered revolutionary at the time and still are widely studied today, and his life is as interesting as his writings”. The Countess was not lying, or even slightly exaggerating: her father, Dr. Nicholas Timasheff, was in fact a world- renowned scholar and author, whose dozens of books and more than 2,000 articles on sociology and other related topics are still read by students of that discipline today, even 48 years after his death in 1970, at the age of 83. And it also seems true, as the Countess contended, that her father’s life was as interesting as were his writings.

Born in Czarist Russia in 1886 to a family descended from a long line of Russian nobility, Timasheff proved his own nobility in the world of academics, earning a doctorate in sociology and, shortly later, a law degree, both from prestigious Russian universities- all before his thirtieth birthday. “My father was one of the youngest people in the history of Russia to earn a doctorate and also a law degree”, the Countess proudly stated.

Timasheff’s life, though, would be shaped more by world events than by his academic achievements. The Communist Revolution took place in 1917, and by 1921, Timasheff, who by then had already published several iconic books and hundreds of articles on sociology, law, and criminal justice, was forced by the new Communist rulers to flee the country, along with his then new bride (The Countess’ mother) and his younger brother. “The Communists hated scholars and independent thinkers”, the Countess explained. “ So my father, under the threat of arrest and execution, fled the country along with my mother and his brother.”

Becoming something of nomads, Timasheff, his wife and brother first immigrated to Germany and then to Czechoslovakia, eventually settling in Paris, France, where they lived from 1928- to 1936- until the growing winds of war in Europe forced him, soon followed by his family, which by then included young Tatiana and his son, Sergei, to move again. This time to America.

It was the country the Countess told me her father loved more than any other. “My father loved America,”, she stated. “He loved the goodness of its people, and he loved the freedom that it provided to all Americans, including those born here, and those like him and his family, who were blessed to be welcomed here as immigrants and later blessed to become American citizens.”

It was the freedom found in America, the Countess told me she believes, which inspired her father – who also was a college professor and guest lecturer in America, and before that in Europe- to write hundreds of more articles and several more books, including his two best known and most time- tested texts. In the first, “An Introduction to the Sociology of Law”, published in 1939, Timasheff postulated that there is an unbreakable interconnection between the law and sociology; and that this (what he argued to be) inextricable interconnection had strongly impacted upon the behavior of both society as a whole and people as separate and unique individuals. As a result of this ground- breaking work, Timasheff was acclaimed by scholars in his field as the founder of the “Study of the Sociology of Law”- an honorary title which he posthumously holds to this day.

In the second- “Sociological Theory, its Nature and Growth”- Timasheff, again as a revolutionary concept, presented the idea that sociologists- no less than authors, teachers and practitioners of other human behavioral based disciplines -had to apply the rules of scientific evidence and methodology to the study of sociology. First published in 1955, the book, for the following four decades, became one of the most frequently assigned readings for graduate and undergraduate sociology students.

While these books further enhanced her father’s standing in the field of sociology, he remained, the Countess recalled, a very modest man. “Of my father’s many books, these two helped him achieve the greatest recognition. But my father was a very humble man, who never bragged about nor even referred to the many accolades he received after these two, or any other book or article he ever wrote, was published and favorably reviewed”, she said.

The Countess’ grandfather, Sergei Timasheff, whom we discussed next, was, according to her, as humble and as brilliant as was his son. Unlike his son, however, his name has been largely lost to history- even though he designed and implemented, as she earlier maintained, one of the world’s first worker’s compensation systems. “All that the Timasheffs and the Bobrinkskoys have accomplished goes back to imperial Russia. And it was in Russia that my grandfather created one of the first worker’s compensation systems in the world”, she stated.

The Countess explained that her grandfather achieved this accomplishment while working for 12 years as Minister of Industry and Trade under Tsar Nicholas II Russia- a descendant of a five- century old dynasty. That dynasty ended with the Russian Communist Revolution in 1917, with Nicholas II, his wife and five children executed the following year by order of the same Communist leaders who were to later force Dr. Timasheff and his family to leave the country.

However, the tragic fate of Nicholas II and his family has been cause of little sorrow for many historians of the Russian Revolution, who have long portrayed him as a weak leader indifferent to the economic hardships endured by millions of his country’s poor. According to the Countess, however, these historians got it only half right. “It is true that Nicholas II was a weak leader,who oversaw a horrible economy and a terribly weak military” she stated. “In fact, Nicholas himself would openly admit that he never wanted to be Tsar because he felt he was unqualified to rule the nation.”

She quickly added, though, that the characterization of Nicholas II as being indifferent to the suffering of the poor was unfair. “He started some major reforms that helped the economy and the working- class poor”, she stated. “He is responsible for initiating a series of agricultural reforms which led to a rise in jobs for farm workers and an improvement in the machinery farmers used to raise crops that helped feed the populace. Also, to protect jobs, he placed tariffs on foreign goods. And, I will proudly add, he put into effect my grandfather’s worker’s compensation system.”

The Countess acknowledged that while her grandfather’s system was less advanced than the one President Roosevelt later began in America as part of his New Deal program in the mid- 193O’s, it did provide some financial assistance for the many Russian agricultural and industrial workers who suffered work related disease or injury, becoming the prototype for other plans that would follow. “My grandfather laid the foundation for all of the workers compensations systems from President Roosevelt on to what over the past 4 generations has been put into effect throughout the industrial world”, she asserted.

Her grandfather, though, was never to see the historical fruits of his labor. As was the common fate for most high government officials who served under the Tsar, the Communist leaders, shortly after they came to power, imprisoned him in a Soviet penitentiary, where he later died.

It was a tragedy, the Countess told me, her father would carry to his own grave. “My father never got over the fact that he was powerless to help his own father get out of prison. He often talked about his great hurt about this, and he spoke about his incredible love for his father until his last days in this world”, she stated.

As significant as were the contributions made to the world by the Countess’ father and grandfather, they seem to pale by comparison to the influence that her husband’s great, great, great grandmother had on the history of the planet. Her story, though, begins very simply. Her husband was named Count Nicolai Alexeevich Bobrinkskoy, and both he and the Countess were members of old Russian families living in exile in America. They met in New York City in 1959 and married one year later. They had two children and remained lovingly together until his death in 2006.

This seemingly common and unexceptional story would end here, except for one incredible historical footnote: the name of Count Bobrinkskoy’s great, great, great Grandmother was Catherine the Great, the longest serving monarch in the history of Russia, who ruled that

nation from 1762- 1796.

“Without my husband’s ancestral grandmother {Catherine the Great}, America would have probably lost the Revolutionary War”, said the Countess. Sounds like a wild claim. But it’s a claim confirmed by history: England’s King George realized by the beginning of 1776 (just nine months after the war began) that America actually posed a real threat of defeating England. So, he penned the following letter to Catherine the Great: “Dear Catherine of Russia: May I please have 20,000 troops to crush American freedom. Regards, George.”

Because King George knew that a cash strapped Russia was in dire need of the substantial amount of money he pledged to pay for the services of these troops, he was said to have been confident that Catherine would agree to his request. But she shocked him by turning him down. It was a decision that many historians of that war believe changed its outcome.

The theory of such historians is that had these 20,000 Russian troops, already battle hardened by their recent victory in a war against Turkey, teamed up with British forces, America would have been quickly defeated. Catherine’s motive though in rebuffing King George has been written off by these same historians as a decision made, not for the cause of American freedom, but rather made to serve her nation’s political interests: Russia and England were both economic and military rival European superpowers at the time, and Catherine believed that an American victory would reduce England’s prestige and influence, benefitting Russia.

To the Countess, though, the motive behind Catherine the Great’s decision not to aid the British is irrelevant. “All leaders make geo- political decisions based upon the best interests of their nations. That is what true leaders of sovereign nations are supposed to do”, the Countess contended. “Ultimately what matters is how their decisions impact upon their own nations and influence the world. And Catherine II’s decision to not aid the British during the Revolutionary War proved pivotal to the eventual victory of the colonists. Nothing historians say can diminish that fact.”

While at first reluctant to discuss her own personal achievements, the Countess herself has done much in her own life for which she has the right to feel very proud. In the past, she co-authored several books on Russian Literature, and served as a college professor of that subject. And now even at the ripe young age of 94, she divides her time between running Zina Studios, a wall paper design shop she started with her husband many years ago, and serving as a volunteer with the Knights of Malta, an international charitable organization, which focuses on providing relief services to victims of natural disasters.

“I am very proud to be able to continue the business I started with my husband. And I am proud to be able to assist a wonderful charity”, she stated.

Still, what keeps her most proud is her two children and four grandchildren. “I want to protect their privacy, so I will not get into the details of their lives”, she said. “Suffice it to say they are all involved in the type of work that would make their ancestors proud…. Through my children and grandchildren the legacy of the Bobrinkskoys and Timasheffs will live on.”

Let’s hope it does.

Robert Golomb is a nationally and internationally published columnist. Mail him at MrBob347@aol.com or follow him on Twitter@RobertGolomb